There is a beautiful synchronicity in two books published recently, each taking a very different perspective on the importance of museums, and together offering a powerful lesson for leaders.

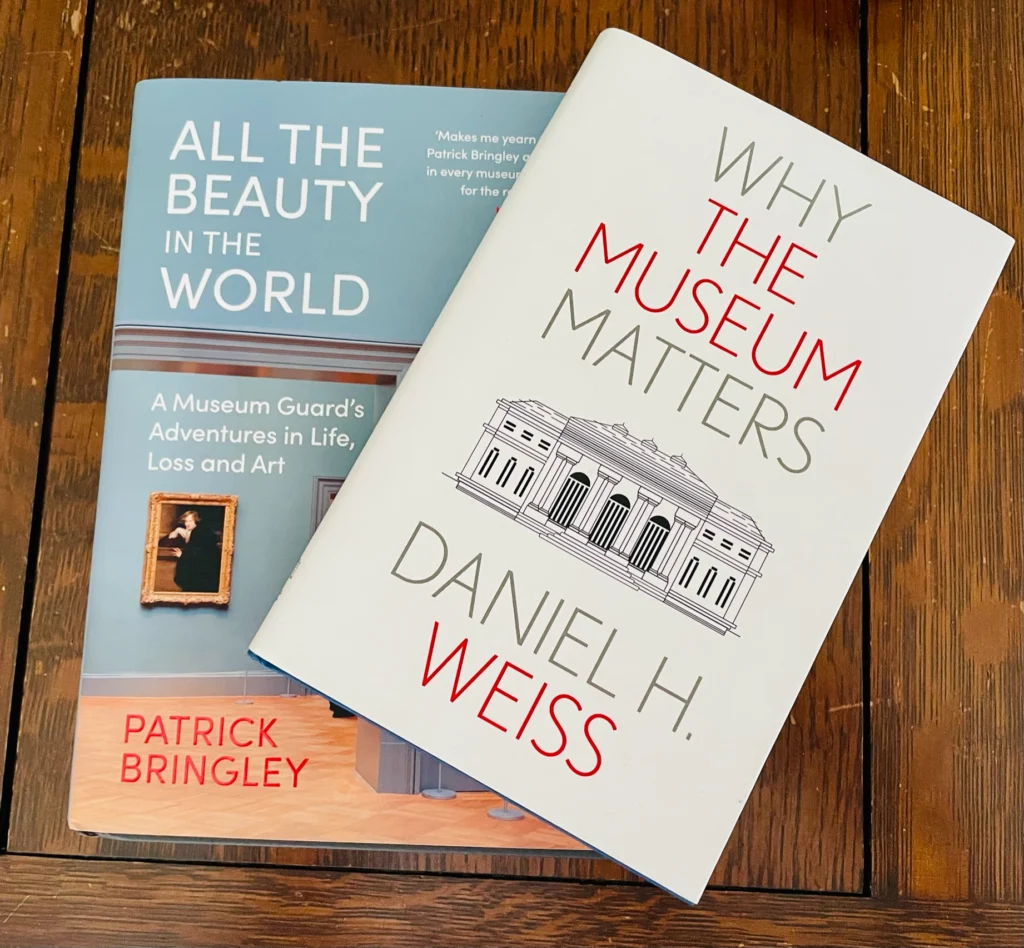

The first is Why the Museum Matters by Daniel H. Weiss, President and CEO of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The second is All the Beauty in the World by Patrick Bringley, a memoir about his ten years working as a guard at that same institution.

Read together, they reveal not only why museums matter, but how differently that value is understood depending on where you stand.

One institution, two lenses

Weiss writes from the top of one of the world’s most influential cultural institutions. His book makes a compelling case for the role of museums in helping us understand other cultures, build empathy, and strengthen democracy.

Alongside that mission-driven argument, he provides a frank account of the realities museums face today: financial pressure, logistical complexity, ethical responsibility, and the difficult conversations surrounding governance, inclusion, and no-platforming. His reflections on the need for museums to include the communities they serve (not just in their programming, but in their mission and governance) are relevant far beyond the museum sector.

It’s a rigorous, strategic view of institutional responsibility.

Patrick Bringley’s book could easily have shared the same title, but its perspective is entirely different.

The view from the gallery floor

All the Beauty in the World tells the story of Bringley’s decade working as a guard at The Met. Through his eyes, we’re taken behind the scenes: into the bricks and mortar of the building, the rhythms of gallery life, the relationships between staff, and the countless ways visitors connect (or don’t) with the art and with one another.

Having recently enjoyed a tour of The Met myself, I was struck by how many locations and works I recognized. Bringley writes with deep affection for the institution, and his observations are intimate, humane, and quietly profound.

His account doesn’t contradict Weiss’s.

It completes it.

Why this pairing matters

Individually, each book distils what we gain by engaging with cultural institutions — and, by extension, what could be lost if we don’t protect them.

Together, they do something even more valuable. They remind us that our definitions of success and failure are not shared universally and that this gap matters.

Despite having KPIs, dashboards, and strategic plans, the way success is experienced and the reasons why it’s judged that way can differ dramatically between those who lead organizations and those who work within them, support them, or are served by them.

Neither view is wrong.

But neither is sufficient on its own.

Museums as a leadership mirror

Museums are particularly powerful case studies because they sit at the intersection of:

- public trust and private funding,

- scholarship and accessibility,

- preservation and relevance,

- institutional authority and individual experience.

What Weiss describes at a strategic level is felt, day by day, in the moments Bringley captures: a visitor pausing, a guard offering reassurance, a work of art making an unexpected connection.

Leadership lives in the space between those perspectives.

The lesson beyond museums

The insight here extends far beyond cultural institutions.

Telling the stories that emerge from personal connections: to our work, to our colleagues, to our clients, and to their experiences of us, is just as important as articulating mission statements and visions.

When we rely solely on metrics, we risk mistaking activity for impact.

When we ignore metrics, we risk losing direction.

The challenge, and the opportunity, is to hold both.

What gives institutions their value

Institutions earn their value when their mission is not only articulated at the top, but experienced meaningfully by the people who work within them and walk through their doors.

Reading these two books side by side is a reminder that value is created not by choosing one perspective over another, but by understanding how they interact and by being curious about viewpoints we don’t inhabit ourselves.

That’s as true for museums as it is for any organization that exists to serve people.