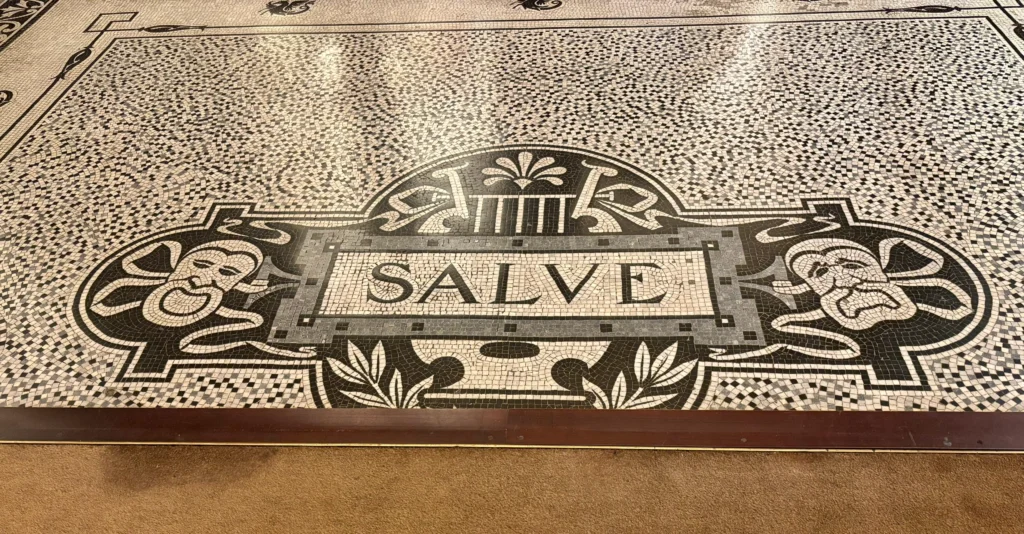

I love a venue tour — especially when it’s a Frank Matcham theatre — so I was delighted to be shown both front and back of house at the London Coliseum, home of English National Opera.

It’s an extraordinary building: London’s largest theatre, rich in history and architectural grandeur. But as magnificent as it is, the visit reinforced something I’ve believed for a long time: the soul of a venue doesn’t live in the building — it lives in its people.

From the moment you arrive at a venue to the moment you step back outside into the real world, it’s the people you encounter who shape your experience. They can elevate it — or undermine it — regardless of what’s happening on stage.

Culture is experienced, not declared

What struck me most about the visit wasn’t just the scale or beauty of the Coliseum, but how deliberately welcome we were made to feel throughout.

That sense of welcome wasn’t accidental. It was consistent, intentional, and clearly shared.

From the warmth of the front-of-house welcome to the knowledge, generosity, and pride shown behind the scenes, the experience felt coherent. Louise Flew and her colleagues didn’t just show us a building — they conveyed the organization’s mission, values, and sense of purpose through their behavior.

Sir Oswald Stoll, the theatre’s founder, would have approved.

This is what strong venue culture looks like in practice:

people who feel valued themselves

people who understand the mission

people who see their role as essential to the whole experience

Culture, in other words, isn’t something you announce. It’s something people feel.

Front of house is not “the front line” — it is the experience

Front-of-house teams are often described as “the front line,” but that framing undersells their importance. They aren’t a buffer between the organization and the audience — they are the organization, in human form.

For most visitors, front of house is the organization they experience.

They:

set the emotional tone on arrival

help visitors navigate unfamiliar spaces

respond to anxiety, excitement, confusion, or frustration in real time

shape how people remember the experience long after the curtain call

In other words, they carry the brand in ways no signage, campaign, or mission statement ever could.

What leaders can learn from great FOH teams

The best front-of-house teams model behaviors that every organization benefits from:

Consistency — the welcome doesn’t depend on who you happen to meet

Empathy — understanding that every visitor arrives with different needs

Clarity — explaining what’s happening without making anyone feel foolish

Pride — in the building, the work, and the experience being created

These behaviors don’t happen by accident. They’re signals of an internal culture that knows what it stands for — and backs that up in practice.

They’re the product of:

clear expectations

good training

trust

leadership that recognizes front-of-house roles as skilled, meaningful work

Why this matters beyond the auditorium

A visitor may forget details of a performance. However, they’ll remember:

how welcome they felt

whether they were treated with patience and respect

whether the venue felt like a place for them

That has implications not just for audience retention, but for reputation, community trust, and long-term sustainability — especially for venues that rely on repeat audiences and deep local relationships.

For venue leaders, the question isn’t whether front of house matters.

It’s whether we’re investing in it accordingly — with time, attention, systems, and recognition.

A reminder worth repeating

Buildings can inspire awe. Programming can move us.

But it’s people — knowledgeable, generous, mission-aligned people — who turn venues into places audiences want to return to.

When a venue gets that right, it shows. And more importantly, it’s felt.